By RuthAnn Deveney

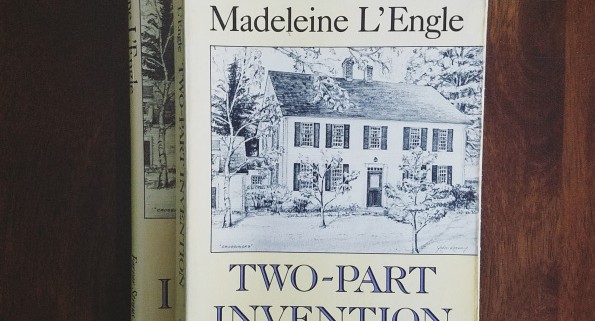

Over the weekend, I re-read Two-Part Invention, which is my very favorite Madeleine book. This memoir is about her 40-year-marriage with actor Hugh Franklin, going back and forth in time between their early courtship and maturing marriage with Hugh’s battle with cancer. It is, as I warn people, very sad.

I probably found this book in late high school or just before college; this is my best guess based on what I had already read from Madeleine at the time. The first section of the book talks about her single life, when she worked as an understudy and stage manager on Broadway while she worked on her first novel. I began to see the connections between the events of her life from her nonfiction and her novels like The Small Rain and Certain Women. By the time I went to college, I was well-versed in her writing and it had had a huge impact on me.

In so many ways, I felt that Madeleine articulated things that I felt, even if I had not consciously expressed them to that point. Two-Part Invention is the most poignant example of that resonance for me, and every time I revisit it, a different line rings in my mind.

I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve read it. Both of my copies are secondhand with brittle pages and weak parts of the spine. The writing feels old, but in a solid, good way. Two-Part Invention was published in 1988, two years after Hugh passed away. At that point, he and Madeleine had been married for 40 years, so now almost as much time has passed since his death (and the publication of the book) as their entire marriage. There are some quaint, “product of the times” aspects to the memories, like writing to book hotel rooms (?) and how Madeleine had to fight to breastfeed her newborns.

But the overwhelming feeling I get from this memoir is its realness. Madeleine talks about the backdrop of war in the sixties; she wrestles with her identity as an atypical housewife (writing was not “real work”); and she confronts the failings of modern medicine. She works through the difficulties of a long, painful illness and then just the beginning of her grieving process. These are universal concepts of the human condition, so the memoir never grows stale for me. Instead, I found myself surprised at how fresh and straight-forward her perspective was. Madeleine is wacky and wandery, but she does not mince words.

This time around, I was drawn toward the passages about difficulty and hardship. I am not naturally a romantic person, and I doubt I was ever swooning over the giddier parts of the book. But now that I have been reading this memoir for at least 15 years, I can see how my mind inclines toward harder topics.

Madeleine talks about prayer — how can she pray rightly for Hugh in his illness? She wants him with her, of course, but he is in terrible pain, and every possible complication does indeed occur. Her weariness and frustration is palpable. I unconsciously clenched my fists and my jaw as I read, only noticing after the fact and then consciously releasing the tension. Part of my response is investment in Madeleine and Hugh’s story; part of it is fear of grappling with this pain and sorrow in my own life. Please, no. But probably, yes, sadly.

As I finished the book, I reflected on why I keep coming back to it. It’s certainly not a 100 percent pleasant experience to read. Some parts are comforting and light: learning about Broadway in the sixties is fascinating, and I love to cheer on young Madeleine as she writes her early novels. But most of it is really tough. Despite that, I think the book is optimistic and life-affirming.

Madeleine says, life is hard, but it’s good. And usually, it’s good because it’s hard.

When my husband and I were dating, as it became clearer and clearer that we might get married, I approached him cautiously about reading Two-Part Invention. He is a reader, but the overlap in our reading taste was and is very narrow. Plus, I was painfully aware that opening up this part of myself to him would make me very vulnerable. I can’t remember how I asked him to read it, and I don’t think I posed an ultimatum, but it was clear that this book (and his liking it) meant a lot to me. Not that we would break up if he didn’t like it, but … well, let’s not think about that. So I lent him a copy and commenced low-grade fretting.

After a time, he returned the book to me. “I liked it,” he said simply. “I feel like I know you a lot better now.”

Relief! And today marks 13 years of marriage for us. I hope that we can be as wise and strong in our marriage as Madeleine and Hugh were in theirs.

RuthAnn Deveney works in corporate learning and development and loves walking around her small town of Kennett Square, Pennsylvania. She lives there with her husband, dog, and a huge collection of Madeleine L’Engle books, including her most prized volume: a signed copy of A Swiftly Tilting Planet, which a friend gave to her in high school after finding it at a yard sale for fifty cents! You can read more Madeleine musings at RuthAnn’s blog or follow her on Twitter and Instagram. This piece was originally published June 25, 2018, on RuthAnn’s blog.

RuthAnn Deveney works in corporate learning and development and loves walking around her small town of Kennett Square, Pennsylvania. She lives there with her husband, dog, and a huge collection of Madeleine L’Engle books, including her most prized volume: a signed copy of A Swiftly Tilting Planet, which a friend gave to her in high school after finding it at a yard sale for fifty cents! You can read more Madeleine musings at RuthAnn’s blog or follow her on Twitter and Instagram. This piece was originally published June 25, 2018, on RuthAnn’s blog.

Do you have something you’d like us to share with our blog readers? We are taking submissions for guest blog posts. Email: social [at] madeleinelengle [dot] com.

As amazing as it is that I remember that moment, I don’t recall reading the book. I remember thinking that I knew the book was true. But I do remember distinctly the next time Madeleine came into my life. I was in eighth grade: rebellious, full of angst, and yet still a reader. One day while browsing the library, the name “L’Engle” caught my eye, and I pulled off the shelf

As amazing as it is that I remember that moment, I don’t recall reading the book. I remember thinking that I knew the book was true. But I do remember distinctly the next time Madeleine came into my life. I was in eighth grade: rebellious, full of angst, and yet still a reader. One day while browsing the library, the name “L’Engle” caught my eye, and I pulled off the shelf  Melissa Giggey spends most of her time reading and writing with teenagers in a classroom and exploring life and adventure as a mom in Gainesville, Georgia, but reads voraciously and writes

Melissa Giggey spends most of her time reading and writing with teenagers in a classroom and exploring life and adventure as a mom in Gainesville, Georgia, but reads voraciously and writes

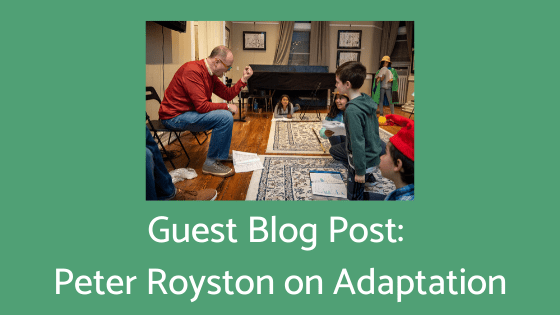

Tarrytown Music Hall in Tarrytown, NY. A theater educator and writer, Peter is the author of over 50 study guides for Broadway, Off Broadway and regional productions, including a series of lesson plans for the A Wrinkle in Time play adaptations at

Tarrytown Music Hall in Tarrytown, NY. A theater educator and writer, Peter is the author of over 50 study guides for Broadway, Off Broadway and regional productions, including a series of lesson plans for the A Wrinkle in Time play adaptations at