Guest Blog Post: Madeleine’s biographer on telling family stories

by Abigail Santamaria

“Tell me a story, Mother…” Madeleine begged many mornings of her childhood, climbing into her parents’ bed before breakfast. Goldilocks and nursery rhymes didn’t interest her—she wanted stories about the Madeleines who came before. The great-grandmother after whom she was named—Madeleine Saunders L’Engle, who died the year before her namesake was born—had danced at the Spanish royal court as a teenager in the 1840s alongside Queen Isabella II and Countess Eugenie (future Empress of France, wife of Napoleon III); later, she served waffles to Robert E. Lee in an adobe hut at Fort Mason, Texas, on the eve of the Civil War. The name “Madeleine L’Engle” was an apt inheritance for a child who would grow to think in far-flung plot lines.

There were other stories, too, about other ancestors who anchored her to a continuum. As Madeleine’s biographer, I’ve read them all. Madeleine’s family tree flowered opulently, lush with lore and Americana, in all its triumphs and sins: Old World origin stories, one-way voyages across the Atlantic, a fateful shipwreck, colonialism, slavery, Revolutionary and Civil wars among smaller scuffles, westward pioneering, and American bootstraps prosperity.

There were other stories, too, about other ancestors who anchored her to a continuum. As Madeleine’s biographer, I’ve read them all. Madeleine’s family tree flowered opulently, lush with lore and Americana, in all its triumphs and sins: Old World origin stories, one-way voyages across the Atlantic, a fateful shipwreck, colonialism, slavery, Revolutionary and Civil wars among smaller scuffles, westward pioneering, and American bootstraps prosperity.

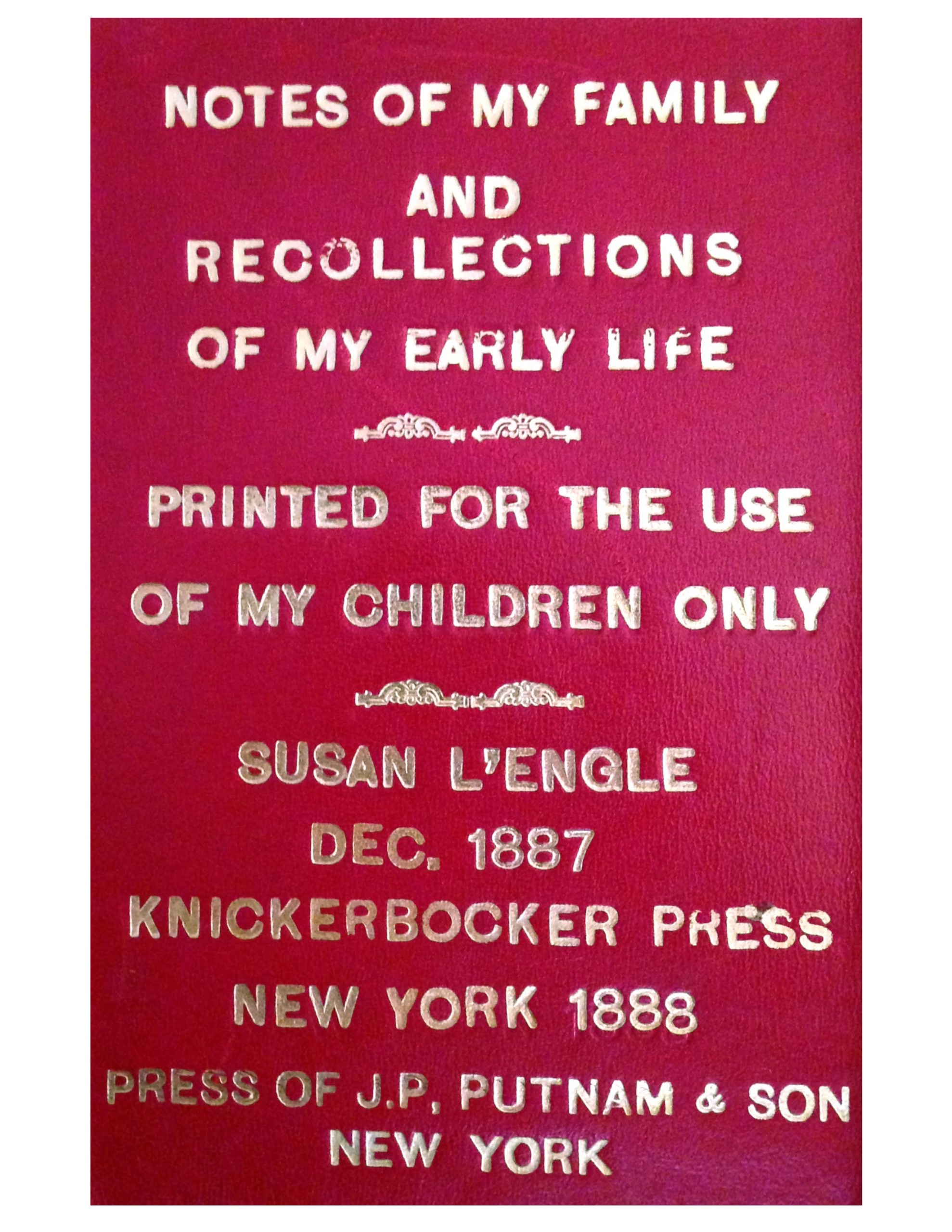

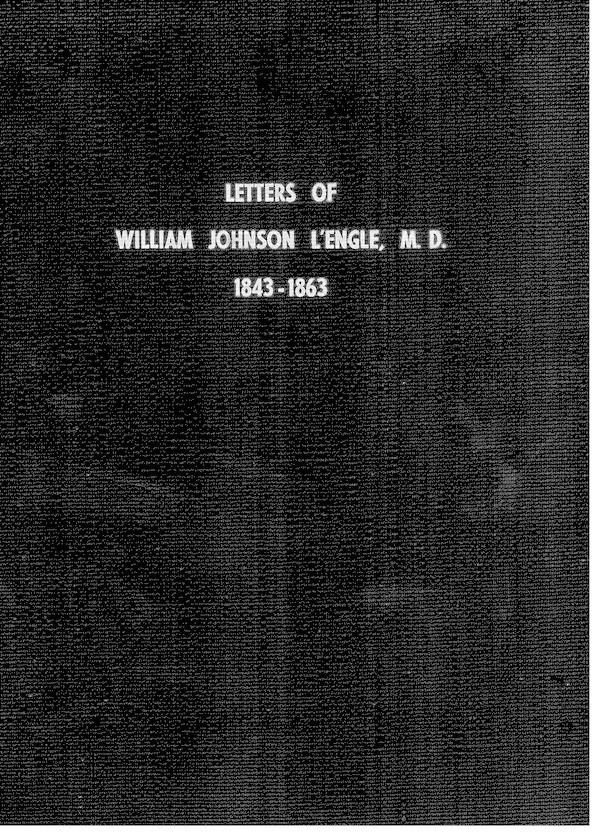

The tales were passed down to Madeleine’s mother primarily through unpublished memoirs written to preserve the family’s history—contemporaneous accounts written by ordinary people. To name just a few: “Notes of My Family and Recollections of My Early Life, Printed for the Use of My Children Only,” by Susan L’Engle (Madeleine’s great-great grandmother), December 1887; “William Johnson L’Engle, MD, (Madeleine’s great-grandfather), by his daughter, Lina L’Engle Barnett, circa 1920; and an untitled 1914 memoir by her grandfather, Bion Hall Barnett, detailing his childhood on the Kansas prairie.

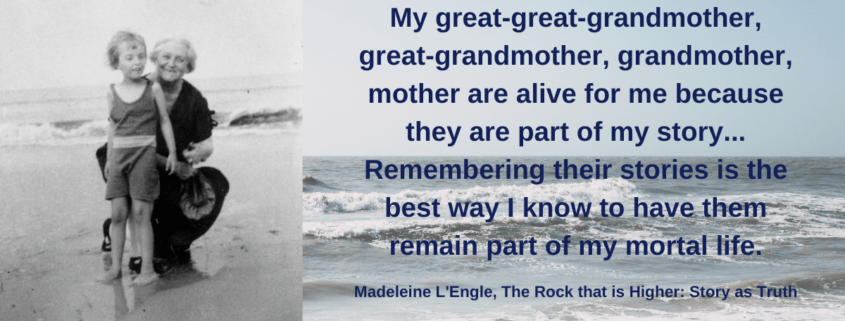

As Madeleine grew up, these texts filling the deep well from which she drew her identity and literary inspiration. In her Reconstruction-era novel The Other Side of the Sun–dedicated to the Madeleine after whom she was named–she named characters after her great-great grandmothers, Anna and Leonis (whose full name was Marie Madeleine Leonis L’Engle). The terrible fire in Ilsa, and the scene in which characters frantically slash treasured paintings from their frames to save them from the flames, comes straight from a relative’s account of the Great Jacksonville Fire of 1901. And, of course, one of her own four memoirs, The Summer of the Great Grandmother, draws on anecdotes from forebears’ manuscripts in an effort to make sense of herself by analyzing and organizing her heritage.

As Madeleine grew up, these texts filling the deep well from which she drew her identity and literary inspiration. In her Reconstruction-era novel The Other Side of the Sun–dedicated to the Madeleine after whom she was named–she named characters after her great-great grandmothers, Anna and Leonis (whose full name was Marie Madeleine Leonis L’Engle). The terrible fire in Ilsa, and the scene in which characters frantically slash treasured paintings from their frames to save them from the flames, comes straight from a relative’s account of the Great Jacksonville Fire of 1901. And, of course, one of her own four memoirs, The Summer of the Great Grandmother, draws on anecdotes from forebears’ manuscripts in an effort to make sense of herself by analyzing and organizing her heritage.

In 1953, Madeleine’s mother followed suit, engaging a woman named Margaret West to write her memoir, “Young in the Eighties: Remembrances of my Childhood.” (That’s the 1880s.) Her preface reads:

To my very dear grandchildren,

From the time your mother was old enough to want me to tell her stories other than Goldylocks [sic] and the Three Bears, her favorites were “When Mother Was a Little Girl.” I realize that my childhood was passed in an era which in its simplicity must seem almost incomprehensible to you—no automobiles, airplanes, radios, moving pictures or televisions. So now, with the help of my good friend Margaret West, without whose encouragement I would never have written these few notes, I am ‘summoning up remembrances of things past,’ hoping you will be interested in ‘When Grandma Was a Little Girl.’

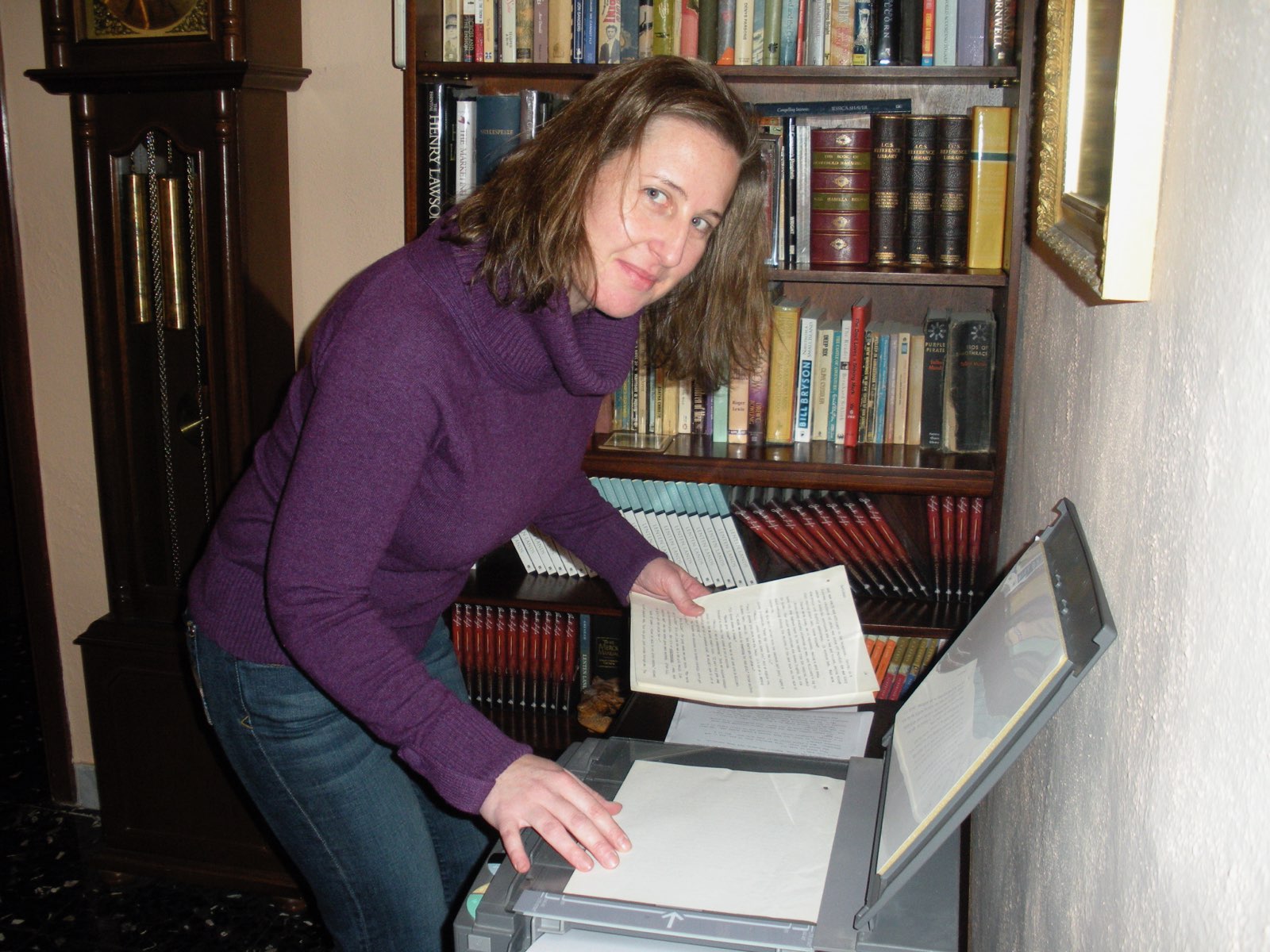

I’ve played the role of Margaret West for many people over the past seven years. Like Madeleine’s non-famous ancestors, my clients understand that everyone’s life story—not just celebrities’—is worth telling for the sake of posterity, catharsis, and self-awareness. I wish I had my forebearers’ memoirs of life during the Civil War, but they may have assumed that their lives weren’t interesting enough. After all, everyone of their generation lived through the Civil War, just as all of us lived through the advent of cyberspace, 9/11, #MeToo. And certainly they didn’t share our 21st century understanding of self-care through self-analysis.

The Summer of the Great Grandmother wasn’t written as a highlight reel of illustrious family history. Madeleine was grappling with how she came to be herself. The Robert E. Lee waffles story didn’t make the cut; instead, she included an anecdote about her grandfather, Bion, nearly losing his leg to gangrene as a child after a whittling accident in Kansas. She chose it because the story illustrated the “measure of courage—and stubbornness” she hoped she inherited from him. “My forebears have bequeathed to me the basic structure of my own particular pattern, both in my cells and in the underwater areas of my imagination,” she explained.

Writing your story—either on your own or “as told to” a professional like me—is an opportunity to claim agency over your rich, complex, fraught history—and to understand your present by examining your past. When your future generations climb into their parents’ beds and ask for family stories, what will your descendants tell them?

Abigail Santamaria

Abigail Santamaria is co-founder of Biography by Design, a boutique business specializing in helping individuals, families and corporations tell their stories in a variety of written formats: book-length memoirs, website narratives, coffee table books, and more. She is a professional biographer of famous subjects, but also believes that everyone has a story worth telling. With her esteemed colleague, Kate Buford, she has extended her skills of interviewing, researching and writing to the broader population. Abby and Kate have been hired to document the lives of parents and grandparents; to write histories of multi-generational family businesses for milestone anniversaries; and to work with individuals who, like Madeleine, are driven by a need to make sense of their lives. (You can find a selected list of their projects here.) Abby is the author of Joy: Poet, Seeker, and the Woman Who Captivated C.S. Lewis, and has written about lives for “The New York Times,” “Vanity Fair,” “Christianity Today,” and other publications.