Guest blog post: The Practical and Transformative Act of Making a Quilt

by J. A. Nielsen

On a cold day in winter, there is nothing I’d rather do than wrap up in a warm quilt with a good book. Maybe a cup of tea. Perhaps that is why I first connected with “Meg Murry” so strongly. In the first lines of A Wrinkle in Time, when the storm outside her windows rages on, she grabs an old quilt.

The brass bed in the attic bedroom at Crosswicks.

Never did I imagine that I would one day be piecing a quilt for “Meg’s bedroom”—or at least the attic bedroom at Crosswicks that inspired Madeleine’s beloved character.

Let’s be clear. It all started as a bit of joke during a webcast from the attic at Crosswicks. And I suggested that the room was missing a quilt! Charlotte and Lena—Madeleine’s own granddaughters, who knew Crosswicks as well as their own homes—asked if I made quilts. Up to that point, we’d only talked about our creative works within the confines of our shared interests—writing. But during the spring of 2020, I was spending much more time with my sewing machine making fabric masks than I was with my laptop. I imagined I could pull some of my collected fabrics and send them a small quilt—something simple in between the practical mask-making. What has resulted became much bigger and took much longer to deliver in person than we imagined. It has also been a great honor.

Madeleine’s dress from which the quilt was made.

Soon after that podcast, a box arrived from Connecticut, having crossed our wide continent to land at my front porch in the Pacific Northwest. Inside was a hand-sewn, vintage tunic-style dress with swirls of bright color and grand floral patterns—purple, turquoise, green, and red outlined on a background of crisp white and black. It was begging to be made into something new.

And yet I balked. Simply pulling the dress from the box felt like a sacred act. And taking a seam ripper to the collar—not to mention scissors—felt like sacrilege.

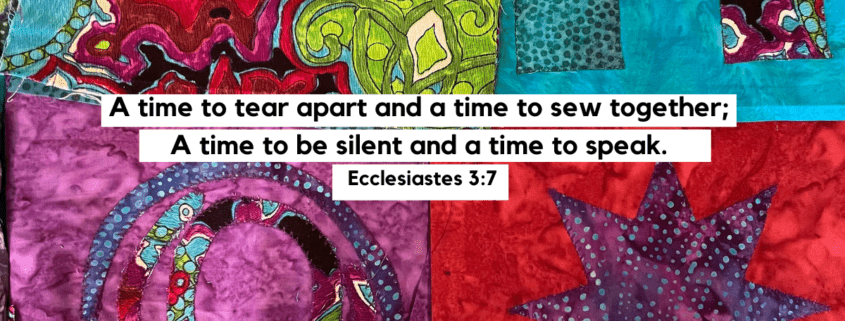

But I thought of Madeleine. And I thought of what she may have to say about making her dress into a thing to be worshipped. She had some strong words about idols. She was also a New Yorker who transplanted her family and learned how to do life in a rural farmhouse. Which meant she knew when it was time to be practical and quilts are a decidedly practical craft.

Creating a quilt is a strange combination of tearing apart and piecing together. It is using and re-using fabrics, so that nothing is wasted or becomes forgotten in the back of a closet. It’s taking something old, maybe even something beloved, combining with new elements and re-fashioning it, so that the result is a new creation. And in that way, quilts are familiar. They provide warmth, both in a literal sense and from the embrace of memory interwoven into the layers.

The lessons I have learned about quilt-making—spoken and unspoken—come from generations of women in my family, many of whom had transplant experiences of their own, where they learned to do life in a new and bewildering place, often facing practical challenges themselves. And they were all whispering to me to get over myself, embrace this lovely invitation—and get to work.

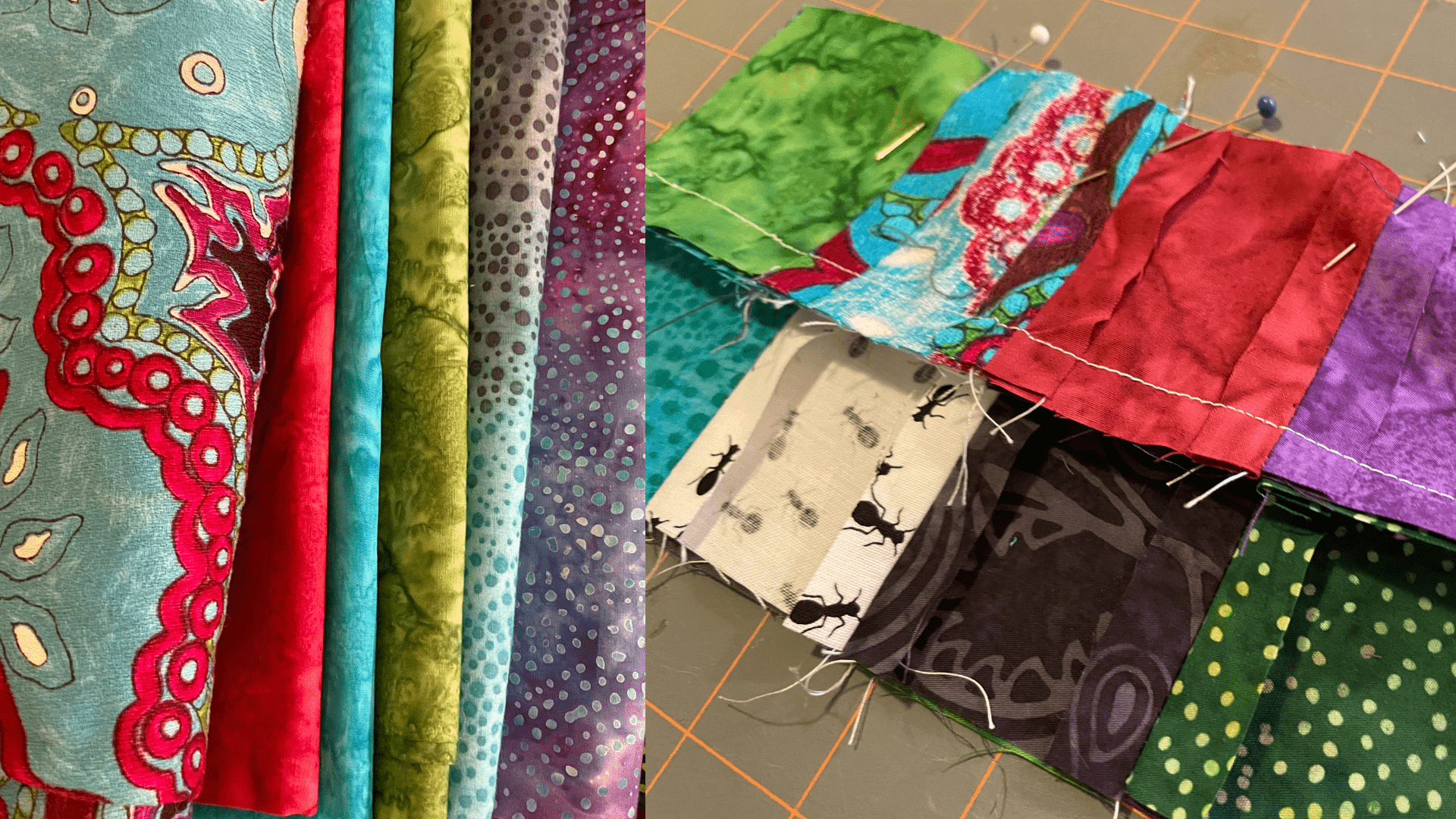

So, I started sketching. When I could go back into fabric shops in person, I took a piece of that collar with me and held it alongside dozens and dozens of fabrics, hand dyed batiks, designer makes, and novelty prints. I made a couple of masks and sent them to Charlotte.

And we waited for the world to open up.

Like crafting a novel, it took time, more time than any of us expected, and many, many hands went into the creation of the final product. I leaned on my son’s innate artistic eye when selecting fabrics to complement the dress material. My daughter is a steadfast accomplice when it comes to creating anything with textiles—sorting, ironing, and layout. And so many hands tied knots to secure the quilt—students and teachers at the middle school where I am a librarian, my husband who put his surgical skills to work, and dozens of attendees at the Circle of Quiet Writing Retreat this past fall—when we could finally all meet in person again after a two-year delay.

A quilt is not a thing that can be made in isolation. In a Circle of Quiet (1972), Madeleine said that stories “come out of a response to what is happening to us and the world in which we live.” This quilt is like that. Even in the time when I was by myself sketching and cutting and piecing, so many people and stories were there with me. I felt their presence as if they were in the room.

Barbara Braver with the quilt and a cup of tea at Crosswicks.

The quilt on the brass bed in the attic at Crosswicks.

And also, like a book, when I give a quilt away, and send it out into the world, it is with the hope that it will be loved by the people I created it for. That it—the small piece of my heart bound up in stitches—will be used and washed and reused, until the blanket itself grows soft, and the colors are muted. I hope it will provide warmth when the world rages outside, and bring comfort—perhaps so that a reader can enjoy their favorite story, even if the cover has also grown soft and pliable with age.

So, thank you to the hands and hearts who helped make this most unique of quilts. Thank you to Charlotte and Lena for entrusting me to lead the effort. And thank you to Madeleine who created “Meg,” the type of girl we can all relate to, who reaches for a quilt on stormy nights.

J. A. Neilsen is the author of the YA Fantasy, The Claiming (Fractured Kingdoms, Book 1), and winner of the 2020 Pacific Northwest Writers Association Literary Contest for Young Adult literature. She has spent most of her professional life in education—as a therapist, teacher, librarian, and administrator. When not writing, she is most likely playing with her family in the forest, on the water, or in the mountains of the Pacific Northwest.

J. A. Neilsen is the author of the YA Fantasy, The Claiming (Fractured Kingdoms, Book 1), and winner of the 2020 Pacific Northwest Writers Association Literary Contest for Young Adult literature. She has spent most of her professional life in education—as a therapist, teacher, librarian, and administrator. When not writing, she is most likely playing with her family in the forest, on the water, or in the mountains of the Pacific Northwest.

Thank you for a wonderful article. I have shared it with several of my quilting groups and all have loved it.