Dear Ones,

Today marks the beginning of Banned Books Week, and so it feels appropriate to share some thoughts that have been brewing about Madeleine and this topic for some time. According to the American Library Association, throughout the 1980s and 1990s, A Wrinkle in Time was one of the most challenged books in the United States. Driven by fundamentalist Christians who reviled her less literal interpretation of the Bible and her vision of a God that welcomes questions and calls us all to love each other no matter our professed faith or categories of identity, the violence and vehemence of the book challenges shook her. Her response was to lean into what she felt was a calling to challenge those forces back. She continued speak at churches and Christian colleges where she wasn’t always welcomed with warm hospitality. (Sarah Arthur has written eloquently about what Madeleine’s message and presence meant to and did for a generation of students and seekers in those worlds in her book A Light So Lovely: The Spiritual Legacy of Madeleine L’Engle).

Madeleine Preaching ca. 1990. Location, photographer unknown

The recent wave (tsunami, really) of organized book challenges is again driven by conservative, white Christians who are threatened by ideas and by visions of a world that includes people that don’t believe as they do. Most of the individual books challenged in 2021 and 2022 have dealt with LGBTQIA+ content, and there has been a separate but related push to censor and limit what can be taught in public schools and elsewhere about the cruel history of slavery and ongoing racism in this country. A Wrinkle in Time is no longer one of the most challenged books, but while it was, Madeleine had some responses that I think might be helpful to consider in our current moment.

In 1983 Madeleine gave a talk at the Library of Congress called “Dare to be Creative.” (The Marginalian has a great essay about it), In it she says:

We all practice some form of censorship. I practiced it simply by the books I had in the house when my children were little. If I am given a budget of $500 I will be practicing a form of censorship by the books I choose to buy with that limited amount of money, and the books I choose not to buy. But nobody said we were not allowed to have points of view. The exercise of personal taste is not the same thing as imposing personal opinion.

My mother and her siblings can attest to the fact that there were certain kinds of books that were not allowed in the house (comic books!), and I have a strong and stinging memory of my grandmother being disappointed (to put it mildly) when she learned that I had written about Flowers in the Attic for an eighth grade book report. But again, “the exercise of personal taste is not the same thing as imposing a personal opinion.” My mother gorged on comics at friends’ houses, with no argument from her parents. What could they say?

Madeleine was horrified at institutions and movements that try to limit free will and choice, that have such a small-minded vision of God that they are afraid of questions and demand certainty. “It is the ability to choose which makes us human,” Madeleine wrote in Walking on Water. People must be free to choose, even if they sometimes choose badly or wrongly. Others cannot make those choices for someone else. It is bad enough when individuals or institutions vigilantly guard their borders: “When we censor out most of the world in order to protect our own little version of it, we are creating a kind of hell.” (Penguins and Golden Calves); it is worse when that little version becomes the basis for violently imposing on others. A growing field of scholars like Kristen DuMez, Philip Gorski, Samuel Hall, and Andrew Whitehead have begun to document and expose a movement that seeks to impose through legislation and judicial rulings a very narrow vision of the United States as a theocracy (White Christian Nationalism), where choices of all kinds are proscribed and state violence as well as vigilantism are enshrined in law.

If Madeleine were alive today, what would she be doing? Where would she be speaking? To whom would she be called to minister? I’m not exactly sure, but I do know that she is still at work through her books that continue to be read, and that she is always on the side of more curiosity, more compassion, more choice.

Photo by Don Hicks.

Charlotte Jones Voiklis is Madeleine L’Engle’s granddaughter and executor of her estate. She is the co-author with Jennifer Adams of A Book, Too, Can Be a Star (October 2022), a picture book biography illustrated by Adelina Lirius; and, with her sister, Léna Roy, of Becoming Madeleine (2018), a biography for middle grade readers. Charlotte has also written and spoken of her grandmother’s work to a variety of audiences. With a PhD in Comparative Literature, Charlotte’s work experience includes teaching and grant making. She is a volunteer mediator.

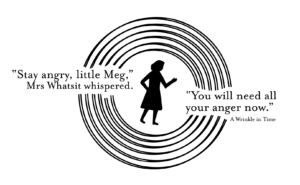

nd if you’re here at the Madeleine L’Engle blog, you’re most likely familiar with the quote from A Wrinkle in Time:

nd if you’re here at the Madeleine L’Engle blog, you’re most likely familiar with the quote from A Wrinkle in Time: said, would help her get along at school, but it was the exact opposite of what she would need to resist the mind control of the evil being IT. Meg’s anger and intractability were seen, by her teachers and herself, as faults, but Mrs Whatsit gave them back to her as a gift:

said, would help her get along at school, but it was the exact opposite of what she would need to resist the mind control of the evil being IT. Meg’s anger and intractability were seen, by her teachers and herself, as faults, but Mrs Whatsit gave them back to her as a gift: