Dear Ones,

This year for Earth Day, I went to Antarctica from my living room chair. Madeleine L’Engle brought me there, through the novel Troubling a Star.

The book, the final in the Austin Family Chronicles, opens with a teenaged, terrified Vicky clinging to an iceberg in the ocean. Before we read about any rescue operation (or even how she came to be floating alone at the bottom of the globe), we travel to the bottom of South America, to a fictitious nation with seriously sketchy plans for the icy continent. From there, Madeleine weaves a dramatic tale of danger, strange and not altogether noble characters, and a little romance. It’s great.

But more, Troubling a Star is proof that storytelling does so much more for activism, for environmentalism, for our imaginations than facts alone can.

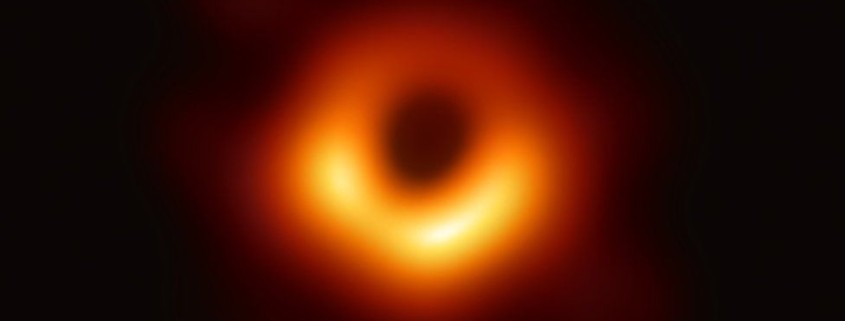

Her story is less “here are pictures of trash in the ocean” and more “(the icebergs) seemed to have an inner light, to contain deep within their ice the fires of the sun from the days when the planet was young.” More awe, less clickbait; more feeding the imagination, less doomsday. It’s just the thesis Madeleine writes about in her nonfiction: story goes a lot farther than facts. For one, stories personify greed and then dares its heroes not to be indifferent — and so, then, the reader. Second, Troubling a Star shows us the beauty of a place most of us won’t ever go; and we’re more likely to care about a place if it’s not just an abstract idea.

In short, you could tweet lines from the book now and sound just as relevant as Madeleine did in 1994. All that’s missing are some hashtags: “Greed is always nearsighted,” and “Without our angels, I believe we would be in a worse state than we are.” And this song — how true:

All things by immortal power,

Near or far,

Hiddenly

To each other linked are,

That thou canst not stir a flower

Without troubling a star.

Madeleine visited Antarctica before writing Troubling a Star, so the details Vicky sees are legitimate. A nonfiction book was born not long after the trip, too: Penguins and Golden Calves: Icons and Idols in Antarctica and Other Unexpected Places.

What a strange thing, to visit a place where tourists just don’t go in big numbers, where animals are threatened and icebergs are melting … all because of the way we use the planet and its resources thousands of miles away. But it’s for this, I think, words she gives a scientist in Troubling a Star.

“The planet has been sending us multiple messages, and the powers that be have ignored them. So it’s up to us, and my guess is that when you finish this trip you’ll feel as protective of this amazing land as I do.”

Tesser well,

Erin F. Wasinger, for MadeleineLEngle.com.

Michigan State University

Michigan State University