Dear Ones,

Happy Spring! It’s hard to trust the feeling of hope and excitement that has been fluttering in my stomach and loosening the tightness in my throat, but I won’t deny it any longer, even if I know there will be disappointments and setbacks. It is ever thus, is it not?

I write to tell you that more of Madeleine’s library will be auctioned this month by New England Book Auctions. They did a test run with a small portion back in December, and raised nearly $10,000 distributed between PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing Program, Smith College (The Madeleine L’Engle Travel Research Fellowships) and The L’Engle Initiative at Image Journal.

New England Book Auctions took on a difficult task. They moved more than 250 boxes of books, sight unseen and content and condition unknown that had been sitting in a (blessedly dry!) basement for more than a decade (more on the why of this later). They sorted and evaluated and inventoried the whole thing (I had queried other auction houses, but they all said they’d be happy to help once I made an inventory myself, which was beyond my power).

I visited last week to look at a few items, pull a few books that had particular sentimental value to our family, and collect several boxes of non-book material that had gotten mixed up in that basement with the other 250 boxes. Paul, the owner, had faithfully set aside photos and letters and even datebooks and manuscripts that were not intended to be part of the charity auction.

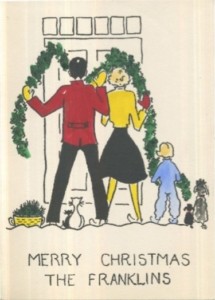

Some memorabilia will be part of the auction, including a photo album of Madeleine Barnett Camp and Charles Wadsworth Camp (her parents) in Europe and Egypt, perhaps on their 1908 honeymoon, but certainly before the First World War. They saw a production of Aida at the pyramids on that trip, can you imagine! There are also old Christmas cards that are hand painted (don’t worry, the full master set is at Smith) that will be offered at the auction.

Some memorabilia will be part of the auction, including a photo album of Madeleine Barnett Camp and Charles Wadsworth Camp (her parents) in Europe and Egypt, perhaps on their 1908 honeymoon, but certainly before the First World War. They saw a production of Aida at the pyramids on that trip, can you imagine! There are also old Christmas cards that are hand painted (don’t worry, the full master set is at Smith) that will be offered at the auction.

The books will be sold in lots on April 8, 13, 20, 22, and 27, but bidding opens early. Lots will vary in size and value.

What took so long? 1) It is a daunting thing when a loved one dies to be responsible for the accumulations of a lifetime. 2) We’re book people! Letting go of books is painful. A bookcase is a record of time spent and history and books are harder to find good homes for than one might think. 3) Her particular status as beloved author made every decision weighted.

I am aware that other authors’ libraries and archives have been sold for very high amounts. Our family made a decision early on that we would not do this. Selling an archive to a library only takes money out of an institution you are trusting to keep something accessible forever, money that could be better used to support students. I think the time it has taken is not only a measure of the immense emotional task but also the time it took build the relationships with the three organizations that will benefit from this sale.

Also recovered from those 180 boxes was a triple strand pearl choker that Madeleine kept in an empty book jacket on a shelf in her nyc bedroom. We had been wringing our hands over it, thinking we had somehow lost it. Though tall, Madeleine had a very slender neck and the necklace never fit anyone in the family except her. Reader, let me tell you: I am taking that choker to a jeweler and extending the clasp so I can wear it. The rest I am letting go.

The secrets of the atom are not unlike Pandora’s box, and what we must look for is not the destructive power but the vision of interrelatedness that is desperately needed on this fragmented planet. We are indeed part of a universe. We belong to each other; the fall of every sparrow is noted, every tear we shed is collected in the Creator’s bottle.

— Madeleine L’Engle, The Rock That is Higher: Story as Truth

Dear Ones,

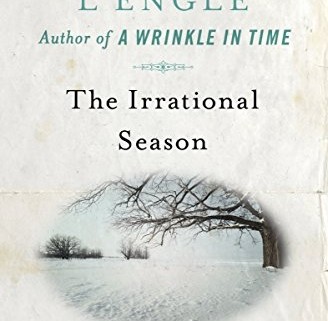

I’ve been finding it hard to find a rhythm for this season. The pandemic started last year around the Christian season of Lent, and now Lent has come back around again. In the meantime, all the other seasons, ecclesiastical and meteorological, have come and gone, and yet the days all seem the same. I have been trying to read through some of the daily prayers in Phyllis Tickle’s series, The Divine Hours, and, last fall, picked up Madeleine L’Engle’s book The Irrational Season during Advent, hoping to find there, as I often have in Madeleine’s work, meaning and resonance from her life that informs the present.

The title of that book comes from a poem Madeleine wrote entitled After Annunciation:

This is the irrational season

When love blooms bright and wild.

Had Mary been filled with reason

There’d have been no room for the child.

But besides finding it hard to find a rhythm for this season, I’ve also been finding it hard to read, to concentrate on themes and ideas, when the stress and fear and grief of this time grips my mind as well as my body. As I wrote here last year, I’ve been falling back on science fiction, fantasy, and young adult novels, that let me forget the harder parts of my life and the world, and inhabit another world for a time. But with non-fiction books, I keep picking them up, reading a page or two, then putting them down again.

So, last fall, I kept trying to get into an Advent-ish frame of mind, kept trying to read, but then it was Christmas, and then Epiphany, and I still hadn’t felt present for Advent. It was autumn, and then winter, and now it’s only a few weeks till spring, and I still haven’t felt fully present for the brilliance of New England’s fall foliage, now long fallen, trees stripped bare.

Still, I keep coming back to The Irrational Season, the book, the poem, and the phrase itself. I think Madeleine used it to mean that God’s ways are wild and different than ours. It was irrational of God to become incarnate in a young, unmarried, marginalized girl, and yet that is where the beauty and power of the incarnation lie. But I keep thinking that this season, this endless pandemic, this terrifying political moment in the United States, is a different kind of irrational season. Irrational as in meaningless. Irrational as in reckless, destructive. Irrational as in evil.

It is irrational that there are clear, simple ways to prevent the spread of a deadly pandemic and people refuse to do them. It is irrational that public health is a political issue at all, irrational for a government to have the resources to help its citizens and choose not to. It is irrational that the poor and starving are pitted against each other when it is the wealthy and powerful that hoard wealth and spend political capital to make themselves wealthier. It is irrational that we do not love each other, when love is the only thing that will save us.

I think of Sporos, the farandola in A Wind in the Door, who fought his deepening into community in favor of selfishness and a false freedom. Sporos ultimately realized that his own life was tied up with that of his neighbors’, and chose the path not only of self-fulfillment but of neighbor-love. Right now it feels like there are millions of Sporoses, making decisions that harm us all, including themselves. And, like Meg, I feel helpless to convince them that all our lives hang in the balance. In the book, Sporos finally understands, finally deepens. But that is fiction. I can escape there, but when I return to reality, to the present moment, what can I do in the face of such continued irrationality? I really don’t know.

I’ve been trying to find a rhythm to this irrational season, but maybe there isn’t one. Maybe it’s outside of the ecclesiastical seasons, outside of summer, winter, fall, and spring. Maybe these really are unprecedented times, and time itself has somehow lost its rhythm. Or maybe it’s something we will only be able to understand in hindsight. Maybe it is something that we have to live through first, and understand later.

In the meantime, dear ones, take care of yourselves, and take care of each other. Be gentle with yourselves, and be gentle with each other. We might not be able to convince others to save us, but we can love each other, as best we can. We can keep vigil for each other as best we can. We can stay present, for ourselves and each other, as best we can. And maybe we will find that we have created a new season, of love, of perseverance, of interrelatedness. A season of a better kind of irrationality than the one we were given.

Tesser well,

Jessica

Dear Ones,

We’re excited to share that registration is now open for Poetry, Science, and the Imagination, the inaugural L’Engle Seminar, hosted by Image Journal, the first in a series of events that will explore the interplay between art and science. This five-part seminar will be held via Zoom at 1pm ET each Wednesday in March. The series was originally planned to launch in New York City last year and then travel across North America in the following years, but of course the pandemic intervened. Instead, the inaugural seminar will be online, allowing access from anywhere in the world!

The L’Engle Seminars are inspired by Madeleine L’Engle’s fascination with the common mysteries that art, faith, and science share. They will explore three aspects of her life and work:

- -Attention to the generative interplay between faith, art, and science

- -Recognition that all art is incarnational and that science enlarges our understanding of creation

- -Generous engagement with diverse faith traditions, including diverse Christian communities.

The inaugural seminar will be hosted by Brian Volck, a pediatrician and poet, and will include talks by Tom McLeish, physicist and author of The Poetry and Music of Science: Comparing Creativity in Science and Art; poet and mathematician Mary Peelen; poet, priest, and Coleridge scholar Malcom Guite; poet and YA author Marilyn Nelson; and poet and educator Robert Cording.

“Poetry and the sciences are connected in deep and surprising ways. Both the poet and the scientist engage reality through the imagination. And in this five-part online seminar, you are invited to explore imagination as a way of knowing within the two disciplines. Each hour-long session will have a distinct focus and feature the insight of a wide array of poets, scientists, philosophers, and theologians.”

To learn more and to register, click here. https://imagejournal.org/lengle/

Tesser well,

Jessica

IT’S THIS WAY

by Nazim Hikmet

I stand in the advancing light,

my hands hungry, the world beautiful.

My eyes can’t get enough of the trees—

they’re so hopeful, so green.

A sunny road runs through the mulberries,

I’m at the window of the prison infirmary.

I can’t smell the medicines—

carnations must be blooming nearby.

It’s this way:

being captured is beside the point,

the point is not to surrender.

Dear Ones,

In 1968, Ahmad Rahman, a member of the Black Panther Party, was set up in an FBI sting and falsely accused and convicted of murder. He spent twenty-two years in prison. During that time he came into a deep Islamic faith, and earned not only an undergraduate degree, but a PhD as well. He also corresponded with our beloved Madeleine L’Engle.

L’Engle and Rahman were one of the first mentor/mentee pairs through PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing mentorship program which aims to “provide incarcerated writers with access to a wider literary community that understands them as serious artists in their own right and welcomes their contributions.” The two wrote each other dozens of letters from 1976 to 1990.

Reading their letters (or rather listening to them in the wonderful dramatic reading below) is a fascinating experience. Here are two people from very different walks of life, yet similar in their determination, their honesty, and their fierce belief in themselves, their stories, and their writing.

There were two moments in their revealed correspondence I found especially profound, and sharply relevant all these years later. The first was when L’Engle asked Rahman what he would like her to call him.

“Would you rather have me call you by the name on the photograph? Amilcar? Names are very important to me, and I feel that our names are one of the greatest gifts we can give each other.”

“Yes. I do prefer that you call me by my real name, Ahmad Amilcar Rahman Sundiata. My friends call me Amilcar.”

“Thank you for giving me your name. I give you mine: Madeleine.”

This Naming felt especially powerful to me, not only because it connected reality to fantasy, evoking Meg’s Naming of Mr. Jenkins in A Wind in the Door, but also because Rahman had changed his name when he converted to Islam. In affirming it, L’Engle also affirmed his faith as an integral part of his identity. I don’t know whether L’Engle ever knew transgender or nonbinary folks, who chose a name for themselves more true than the one they were given, but this exchange makes me think she would have wanted to know their true, chosen name, and would have taken that name, also, as a gift.

Another moment, for me, that speaks across the years is when Rahman critiques parts of L’Engle’s book, The Other Side of the Sun, specifically her depiction of Black characters in a book set in the American South in the early 1900s. After explaining the parts he doesn’t like, Rahman adds,

“But you mean well. That’s what gets me. I mean you mean so well. And all the condescending passages are unintentional. You just didn’t know how to express what you wanted, and what definitely needed to be expressed. If there’s one thing I deeply want you to gain from my friendship, it is the ability to express your ideas and feelings about this swirl of racial conflicts in a fashion that puts to use your considerable gifts for the good you strive to do.”

L’Engle responds simply, with gratitude and without defensiveness.

“Well, you’re teaching me a lot. I don’t think I want to ‘mean well.’ The road to hell is paved with good intentions…Don’t ever hesitate to push me into wider and deeper thinking.”

As a writer myself, and also a white woman, I can say that my writing and my striving to not be racist are probably the two subjects most difficult to receive critique on with equanimity. But how often in the last few years have we seen the damage that can be done when white women handle critique poorly, using their tears to gain sympathy, and insisting that they meant well and that intention matters more than the effect of their words and actions?

But L’Engle doesn’t react defensively – or if she does, she deals with it on her own and doesn’t ask Rahman to pamper her. She wants to be a better writer, and she wants to be a better person, so she welcomes Rahman’s critique, and thanks him. What a great example for us in 2020 of allowing ourselves to be “called in” to anti-racism work, rather than feeling “called out” by honest critique.

***

In September, 2020, Pen America announced the first class of the L’Engle/Rahman Prize for Mentorship, named in honor of their friendship and underwritten by L’Engle’s family. The prize honors four mentor/mentee pairs in PEN America’s longstanding prison writing mentorship program, which links established writers with those currently incarcerated. Hundreds of mentor/mentee pairs participate in the program every year, and these four have been chosen as modeling the ideal of the program. Those chosen,

“…exhibit the spirit of the L’Engle-Rahman exchange—committed and consistent communication, feedback that honors the writer’s intention and unique voice while being open and honest in rigorous critique, and a demonstrated dialogue between both writers on craft and intellectual ideas.”

You can read the fascinating essays of the four pairs of winners here.

As I read them, I was struck by how different all eight individuals were, and how different each pair’s chemistry as partners. Benjamin Frandsen and Noelia Cerna offered each other intellectual camaraderie and emotional grounding. Elizabeth Hawes and Jeffrey James Keyes dug into the nuts and bolts of writing and producing a play. Derek Trumbo and Agustín Lopez created space for frightening words to be fearlessly shaped into stories. Seth Wittner and Katrinka (Kei) Moore united in their belief of the power of writing, both in poetry and in prose.

But one theme that was common in each of their stories was that the mentors learned as much from the mentees as the other way around. These are creative, constructive relationships between individuals who are all imperfect, but all striving to create something worthwhile, something beautiful and true, out of their experiences and their lives, to push forward through the past and the present, and to create the future with their own pens.

As the Turkish poet and political prisoner, Nazim Hikmet, wrote,

“It’s this way:

being captured is beside the point,

the point is not to surrender.”

Tesser well,

Jessica

Dear Ones,

2020, apart from the collective traumas of covid-19 and the election, also marked the 13th anniversary of Madeleine’s death and the 102nd anniversary of her birth. She loved celebrating her birthday, November 29, and often bemoaned its coming too close to Thanksgiving. I have intense, impressionistic memories of Thanksgiving as a child: crowded tables, the clanging of silver and china, adult laughter and conversation, being allowed to light and snuff the candles, and staying up late. Sometimes we gathered as a family and assorted friends in New York at my grandparents’ apartment near the Cathedral of St. John the Divine; sometimes at their home in Northwestern Connecticut, Crosswicks. This year our gathering was tiny compared to years’ past, only the five of us that make up our current quarantine pod, but it was at Crosswicks, and we are grateful.

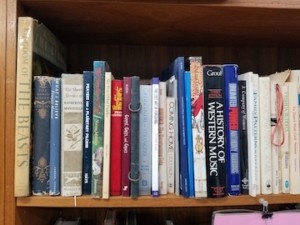

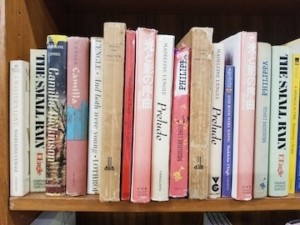

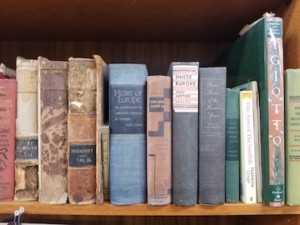

We’ve been at Crosswicks since March and have watched the seasons change and our expectations shift. I have gotten some good work done, but have also been amazed by what remains unfinished. One thing I am very happy to announce is that Madeleine’s library of approximately 10,000 books has been collected, sorted, and arranged by New England Book Auctions and will be on sale in various stages over the next several months, proceeds going The Madeleine L’Engle Travel Research Fellowships Fund at Smith College, PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing Program, and The L’Engle Initiative at Image Journal.

The 258 boxes of books came from Crosswicks and her home in New York, and have been in storage since her death, nearly thirteen years ago. It was a great deal of work to go through them and make decisions, and we were finally able to tackle it this summer. It was not easy finding an auction house that would take this on: because the boxes had been in storage so long, their condition and value was unknown and I did not have the capacity to do an inventory. New England Book Auctions was able to make 3 trips to pick up the boxes (thank you, Connor, who made those trips and navigated the ancient and low cellar!) and has started to go through the books and arrange them in lots for sale, the first several of which are live on their website now, and bidding ends on December 3.

Madeleine in the Tower, ca. 1958

The first lots are “shelf sale” books, and have about 100 books in each, designed to be of interest to book dealers and not necessarily individual buyers (though you’re welcome to browse and bid!). Some are signed by her, some are by her, and all come from her personal library which was acquired over her lifetime. Some of the volumes originally belonged to her mother and father and other relatives but were on her book shelves. The books currently on sale represent about ten percent of the total, so there is much more to come, including a catalog sale of higher-value volumes. Do take a look if you’re curious. I love seeing her copies of The Lonely Crowd, The Life and Works of Sigmund Freud, What Is Science?, and Ship of Fools.

Dear ones, this is painful. Letting go of books always is, and these are very special, so it feels I’m letting go of her, too. Along with the pain of letting go also comes a sense of relief and freedom. It’s intense though, and I’m taking deep breaths. I hope you are, too, in the midst of all the changes all around us these days.

Charlotte

Reposted from Sarah Arthur‘s facebook page, with permission.

Dear ones,

One year ago today I was wrapping up a glorious weekend co-directing 2019 Walking on Water: The Madeleine L’Engle Conference held at All Angels’ Church in NYC. A truly fantastic team of authors, musicians, visual artists, filmmakers, theatre educators, writing teachers, editors, booksellers, creatives, and nearly the entire church staff…everyone made it an unforgettable weekend–which is all the more poignant in retrospect, knowing now what we didn’t know then.

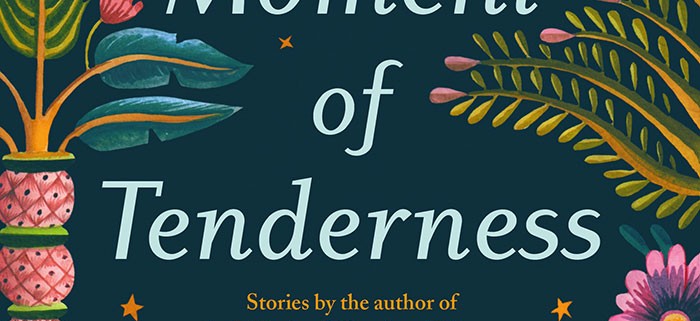

Madeleine L’Engle’s granddaughter, Charlotte Jones Voiklis, you are still pure magic (also sending virtual hugs to YOU, Léna Roy!), while M’s dear friend Barbara Braver has become one of those wise women I didn’t know I needed in my life. Katherine Paterson’s keynote “The Water is Wide” still rings in my ears, as does Audrey Assad’s music (“The Irrational Season,” anyone?). Madeleine’s new short story collection, “The Moment of Tenderness,” lovingly compiled by Charlotte and released in April, comforted us in those early dark days of the pandemic, while the new edition of M’s collected poems, “The Ordering of Love,” (with a foreword by yours truly) graced us too. If anything, these voices have grown more resonant.

There have been difficult changes along the way. NYC is a vastly different city now. Our nation is reeling from ongoing political destabilization–a situation that Madeleine understood all too well during the McCarthy era. Some of us are unemployed or underemployed or simply too overwhelmed to create much of anything right now (*raises hand*). Others have taken care of–or lost–loved ones during this dreadful pandemic, and/or fought the disease themselves. To our NYC friends, especially, and others who’ve had to move or change jobs: we send all our love and prayers.

There’s also much to celebrate! Sophfronia Scott is now the director of the first-ever Alma College MFA in Creative Writing (congratulations!), while the phenomenal team from We Need Diverse Books continues to add to our stack of nightstand reading (Sayantani DasGupta, you’re a total rockstar!). So many of these creatives have released new titles/films/stage-plays/music/events in the past year (Karina Yan Glaser’s new Vanderbeekers book and Peter Royston’s stage adaptation of M’s “A Wind in the Door” are both delightful); and several have marked major milestones (Joyce Yu-Jean Lee got married, y’all!). Without these things our world would be a darker place.

Dear Ones, though it’s been a year–and such a year–our hearts remain full. We’re in this together, and I can’t wait for the day when we’ll reconvene once again, to press forward in creativity and hope. In the meantime, as Madeleine said, “Like it or not, we either add to the darkness of indifference and out-and-out evil which surround us, or we light a candle to see by.” Light all those candles and together we’ll blaze out into the universe!

by Jessica Kantrowitz

Dear Ones,

I’ve all but given up reading non-fiction lately. I’m too saturated with reality, too overwhelmed with a never-ending news cycle that keeps my mind in fight-or-flight mode constantly. There are so many good writers right now grappling with questions of faith, trauma and healing, parenting, social justice, and racial justice, and I keep buying their books, but when I open them to read my mind is a fog.

The problem is, I’ve reread all the books I keep by my bedside too recently for another reread, including Madeleine L’Engle’s Time Quintet – A Wrinkle in Time, A Wind in The Door, A Swiftly Tilting Planet, Many Waters, and An Acceptable Time. You know how you can tell in your gut if it’s time yet or not? So a couple of months ago, when the libraries in Boston finally opened again for socially distanced pick-up, I sat down at my computer and Googled, “best young adult fiction of all time.” I needed new-to-me books that drew me in as well as my old standbys: The Arm of the Starfish, Watership Down, A Wizard of Earthsea, The Princess and the Goblin.

I felt like a kid again when I began to receive notifications about the books I’d requested. If I could have, I’d have hopped on my bike instead of in my car to zip over to the library, lingering in the nearby woods when I kept arriving before they were open. Then — what treasure! The heartwarming The Vanderbeekers of 141st Street by Karina Yan Glaser wrapped me up in the charm of New York City. Howl’s Moving Castle by Diana Wynne Jones blurred the lines between fantasy and fiction. Everything Sad is Untrue by Daniel Nayeri, though technically nonfiction/memoir, enthralled me with stories both ethereal and earthy. Yet in all of these books, as in Madeleine’s, the escape into fantasy was also a way to process the seemingly impossible challenges of reality.

“A child who has been denied imaginative literature is likely to have far more difficulty in understanding cellular biology or post-Newtonian physics than the child whose imagination has already been stretched by reading fantasy and science fiction.”

Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art

I’m not the only one who has been leaning into fantasy lately. On October 15th, TIME Magazine published a list of the 100 best fantasy books of all time. When I saw it, I immediately opened another tab with my library’s request form. TIME asked fantasy authors Tomi Adeyemi, Cassandra Clare, Diana Gabaldon, Neil Gaiman, Marlon James, N.K. Jemisin, George R.R. Martin and Sabaa Tahir to nominate books, then rate the 250 nominees on a scale. TIME’s editors then considered elements such as “originality, ambition, artistry, critical and popular reception, and influence on the fantasy genre and literature more broadly” to come up with the final list.

“A story where myth, fantasy, fairy tale, or science fiction explore and ask questions moves beyond fragmatic dailiness to wonder. Rather than taking the child away from the real world, such stories are preparation for living in the real world with courage and expectancy.”

Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art

A Wrinkle in Time is on it, of course, along with A Swiftly Tilting Planet, and a host of my other favorites. (If you haven’t read The Princess Bride, may I say that the book is even better than the movie.) The first two, The Arabian Nights and Le Morte D’Arthur, made me feel a little guilty for never finishing them. Maybe someday. But perhaps most exciting were the newer books I was less familiar with. Shadowshaper by Daniel José Older went on my “requested” list right away, as did The Wrath and The Dawn by Renée Ahdieh and Children of Blood and Bone by Tomi Adeyemi. I can’t wait to zip over to my little library by the woods to pick them up.

And do you know what? I just got that feeling in my gut about an old favorite. It’s time to reread The Arm of the Starfish again. I’m adding it to my list.

What’s on your list?

Tesser well,

Jessica Kantrowitz

Blog debut of Jessica Kantrowitz for madeleinelengle.com. Jessica Kantrowitz writes about faith, culture, social justice, and chronic illness, including her own struggles with depression and migraines. She has worked as a storyteller for Together Rising, and her writing has been featured in places like Sojourners, Think Christian, The Good Men Project, and Our Bible App. Despite having earned a Master of Divinity, she still feels very much like an apprentice. Her first book, The Long Night: Readings and Stories to Help You through Depression is available wherever books are sold, including your local, independent bookstore.

Dear ones,

The response to the short story collection The Moment of Tenderness has been wonderful — I knew that I loved these stories and saw something in them, and that others do too is such a beautiful thing. There have been several notable recent reviews, including from The New York Times, The Christian Science Monitor, The Associated Press, and Hypable, and four stories are available for free right now:

- The Fact of the Matter from the publisher (a horror story)

- Summer Camp at Salon (the short story that prompted her first editor to enquire about a novel)

- A Room in Baltimore at LitHub (fans will recognize this story from Two Part Invention)

- Charlotte’s introduction to the collection at The New York Times (please read this: it sets the stage for understanding the individual stories and the collection as a whole).

Also, there’s a podcast! You can hear archival audio of Madeleine herself, as well as my conversations with Jamie Quatro (author of I Want to Show You More and Fire Sermon) and Karen Kosztolnyik (editor at Grand Central Publishing).

I’ll be doing a Facebook Live broadcast on Thursday, April 23 at 12:30PM. Tune in if you can! I’ll be coming to you from an attic bedroom at my grandmother’s house “Crosswicks” in Connecticut, a bedroom we always thought of as Meg’s room, complete with a ping-pong table and brass bed (no patchwork quilt, alas).

“Meg’s attic bedroom”

It’s a difficult time for everyone, though certain people are more affected than others (front-line workers, the incarcerated, communities of color), including small businesses and their employees. Bookstores fall into that category, and so I encourage you to show your love for books by supporting your local indie bookshop. You can do that by ordering books directly from your favorite, using bookshop.org, contributing to Save Indie Bookstores.

Stay well and safe and connected.

Charlotte

Earlier this week I relished a custard-filled pączki, just on time. You can set your watches to these Polish fried dough things showing up in Midwestern convenience stores, just in time for Fat Tuesday. By Wednesday they’ll grow stale (and half price!). See, Wednesday (Feb. 26) marks the beginning of Lent.

Lent is the 40 days (minus Sundays) before Easter, when some Christian traditions generally prepare themselves for Holy Week and Easter. As you might guess, Lent’s a lot less fun than prepping for Christmas. As someone who attended an Episcopal church, Madeleine recognized the timbre of the church’s calendar year. She writes about this in the third Crosswicks Journal book, The Irrational Season, the audiobook that I’m listening to now.

Serendipitously I’ve landed in the book’s chapter on Lent, which Madeleine aptly calls a “strange bleak season.”

(And aren’t her February feels right on point: “How right the Romans were to make it the shortest month of the year.” And March? Don’t get us started.)

It’s traditional to give up some vice or comfort during Lent, maybe chocolate or that glass of wine after dinner. But Madeleine, I think, lands on something more true about this season. Instead of giving up petty, favorite things, she thinks about the demands made on her, “that I’m not sure I want made.” She goes into the Beatitudes, sweeping from the meaning of the word “blessed” to the kind of God who’d think up a thing like Easter. And though I want to rush ahead to the marshmallow bunnies part of Easter, Madeleine teaches us readers not to miss what has to come first.

“Here the world’s in the worst mess we’ve been in for generations, and we no longer get down on our knees and say, I’m sorry. Help! … the Confession must come before we can rejoice.”

(The timeliness of her words … what is that quote? “A classic is a book that has never finished saying what it has to say.” Yes, that.)

Another to consider: her poem “For Lent, 1966.” You can read her poem in its entirety in the newly re-released book of poetry, The Ordering of Love, but the first two lines capture that idea of doing Lent differently:

Another to consider: her poem “For Lent, 1966.” You can read her poem in its entirety in the newly re-released book of poetry, The Ordering of Love, but the first two lines capture that idea of doing Lent differently:

“It is my Lent to break my Lent,

To eat when I would fast …”

Do you observe Lent? What are your favorite poems or books for this strange season? Share them in the comments!

Tesser well, even in the longest of Februaries,

Erin F. Wasinger, for MadeleineLEngle.com.

Error: No feed found.

Please go to the Instagram Feed settings page to create a feed.